Long-shore currents form when the surf hits the beach at an angle, causing the water to move faster and faster along the shore. They aren’t a big deal if you’re aware of them. But it took two experiences—one financially painful, and the other physically exhausting—for me to learn this lesson.

My financially painful experience was during my wind-surfing days in the mid-80s. I got into windsurfing early in the sport’s trajectory, at least on the East Coast. I learned in South Carolina, on Lake Hartwell first, and then in the ocean off Folly Beach with a guy who had one of the first one hundred “Windsurfers” ever made. (The term “Windsurfer” was actually the brand name of a sailboard manufacturer.) Being able to jump and surf waves on a sailboard was a blast. When I moved to Ocean City in the early 80s sailboarding in the ocean was just catching on.

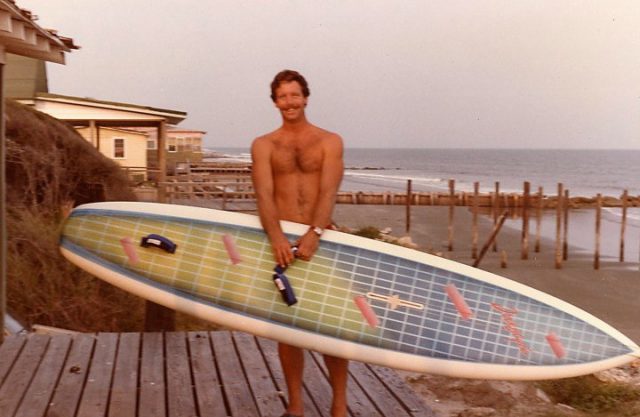

Windsurfing in Ocean City in the early 80s.

At that time I was riding a “sinker” which was a short sailboard. More like a long surfboard, it required a lot of wind for it to work, and similar to a slalom water ski if you didn’t have enough speed, you just sank. When you fell, you had to perform a ‘water start’: Lying in the water, you’d hold up the sail. When the wind caught the sail, it would lift you onto the board. The maneuverability of these small boards made them perfect for surfing.

My first sinker sailboard Folly Beach, SC

(One of my first “learning experiences” on a sinker sailboard was when a friend of mine and I attempted to windsurf to Fort Sumter from the battery in Charleston Harbor. We were on our sinker sailboards when the wind died. It was well after dark by the time we drifted/paddled into the commercial shipping port and found a place to get out of the water. But that’s for another “learning experience” blog.)

Back to Ocean City. In those days, the Ocean City beach looked a lot different. The waves broke off-shore, not directly on the beach like they do now. There was enough room to launch in fairly flat water and get your speed up before you hit the waves.

The conditions on this day were OK. We’d had a north wind for a few days, which made for a decent swell. The head-high waves looked great, but it was only blowing about 15 knots. 15 knots was about the minimum for riding my short board, but I figured it was doable.

I did a beach start (pointing the board east and jumping on it while pulling in the sail to get speed). Although upright, I wasn’t moving fast enough. The first wall of whitewater hit me and knocked me over. About one hundred feet from shore, I attempted several water starts before realizing that I wasn’t going to get up.

Just then, I looked up to see that I was heading straight towards a semi-submerged rock jetty. No time to react – my board, rig, and I all got washed across the jetty. I didn’t get hurt. But my equipment got trashed.

The persistent north winds had created a strong long-shore current, about five knots. The current running the same direction as the wind meant that the apparent wind (the wind that my sail felt) was about ten knots—nowhere near enough to get out through the surf.

That was an expensive lesson.

My physically exhausting experience was while surfing in Puerto Rico. I was staying on the northwest corner of the island, in the Aguadilla area, and had gone surfing at a break called Wilderness. This surf spot had big waves, but they were mushy, meaning they were forgiving, not too powerful.

A fortress of sharp, volcanic rocks guarded the space in between the beach and the surf. One little path through the rocks, called a keyhole, allowed access to the water. Getting out to the waves wasn’t a problem. You waded through the keyhole, waited for a surge, hopped on your board, and paddled out. The only problem was that, to come back in, you had to line yourself up with the keyhole.

The waves were great, and I surfed my brains out. Getting pretty tired, I decided to head in. I paddled towards the keyhole. But as I got nearer, the long-shore current caught me. I watched as the exit point sped past. No matter how hard I paddled, I couldn’t make it back to the keyhole. After struggling against it for a few minutes, I gave up and let it sweep me down the shore. I had to paddle back out through the surf, beyond the waves, way up current, and then try again.

Although worn out, on my next pass, I didn’t miss the keyhole.

Whether kayaking, paddle boarding, sailing, or just swimming in the ocean, knowing the speed and direction of long-shore currents is helpful. You can see the direction and estimate the speed of the current by watching the waterline, noticing how quickly the foam or other detritus moves sideways along the shoreline. If you’re launching a kayak or paddle board, instead of going straight out from the beach, point into the current. Otherwise, it will hit your bow and swing your boat parallel to the waves, leaving you in a vulnerable position.