I’d read that the Loxahatchee River was best suited for intermediate paddlers in nine to fourteen foot kayaks because of the narrow, twisty nature of the river. The reports also said that many people, instead of trying to arrange a shuttle for a one-way trip, did out-and-back trips, meaning they’d be paddling against the current for half of the journey. I consider myself intermediate and, even though my kayak is sixteen feet, I felt pretty confident. Mitch had agreed to drop me off and pick me up. I’d be going with the current. It should be an easy trip.

But as I flew downstream with the current, muscling around sharp curves, grabbing onto logs and branches to keep from getting pinned against deadfall or wedged between cypress knees, I thought two things: 1) I am a complete spaz, flailing around like it was my first time in a kayak; and 2) I would NOT want to paddle against this current.

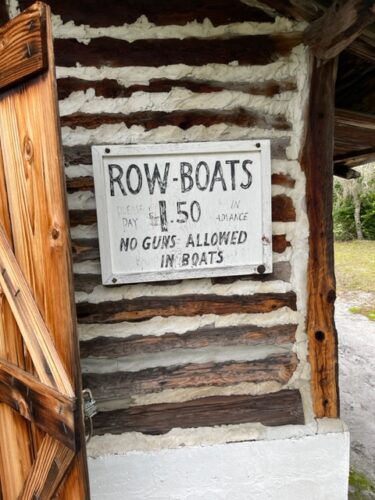

I’d passed a rental concession near the launch with stacks of beginner friendly sit-on-top kayaks. Would they really send novice paddlers down this? Then again, I hadn’t seen a soul on the river since the very beginning, when I’d passed a group of renters paddling the opposite direction, asking if I’d seen any gators. Here I was in South Florida in January. Restaurants, bars, roads, grocery stores, gas stations, bike trails, campgrounds, shopping areas—everything was packed. Yet, I was the only person on this well-advertised water trail. Had I missed something?

I was the only person at the launch. Hmmm…was there something I didn’t know?

The Loxahatchee River is one of two rivers in Florida with the Wild and Scenic River designation. Passed by Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act protects the waterway from federally licensed water development projects, and protects its water quality along with other values deemed outstanding. Less than one half of one percent of our nation’s rivers have this designation and the protection that comes along with it. In Delaware, 94.7 miles of White Clay Creek and its tributaries (spanning both Pennsylvania and Delaware) received this designation. And although Maryland has 16,839 miles of rivers, it has no Wild and Scenic designated rivers.

The entire Loxahatchee basin is 210 square miles. The protected portion is 7.6 miles. But this small section was like paddling through a time warp.

Hugh Baldcypress trees, some 500 years old, lined the banks. Spanish moss draped off branches, swaying in the breeze, covering the Resurrection ferns, curled and brown, waiting for the next rain to come back to life. Green and pink bromeliads poked from limbs and crevasses—anywhere their roots could anchor the top-heavy beauties. Palm trees crowded the banks, obscured the sky, and leaned out over the river. Ephemeral Swamp lilies appeared here and there along the route.

Tannin-stained water, the color of over-steeped, overly sweet, Southern ice tea, swirled and churned under my kayak, bubbles rising to the surface occasionally from who knows what. I saw four Little blue heron morphs, two alligators (one little, bitty guy and one plenty big enough to scare me), lots of Kingfishers and Great blue herons. At one point, I glanced down and was startled to find myself drifting over a large cement culvert only an inch or two beneath my kayak. Then the culvert moved. It was a manatee and her baby!

The manatees were downstream from two small dams—more like spill-overs. I’d read about them in the description but was still disappointed to see them. I’d thought Wild and Scenic meant that there’d been no human “messing around with”. But there are different levels of “wild” within the Wild and Scenic designation.

You could hear the dams in plenty of time to get nervous about them. They both had portages—wooden decking allowing you to exit and pull your kayak past the obstacle before entering again. Or you could paddle over them and enjoy a short whitewater thrill. A little Mitch on my shoulder said, “This looks fun—go for it!” But my chicken-liver heart said, “No way.” (When I got back and showed Mitch my pictures of the dams, he said, “I can’t believe you didn’t paddle over them. They’re so small. What were they, like six inches?”)

After about four and a half miles of sliding out from the one line that would get me around the curve or through the deadfall, hard forward sweep strokes followed by reverse, reverse, reverse, and botched bow draws followed by forward sweeps and again, reverse, reverse, reverse, I came upon an old dock with a tin-roofed boat house. I’d been looking for this. It was Trapper Nelson’s Zoo and Jungle Gardens. Or it had been. Now it is a historic site within the Jonathan Dickinson State Park.

Nelson came to Florida in the 1930s and bought land on the Loxahatchee, determined to become a hermit. But instead, he became a legend, sought after by locals and tourists alike. People hired boats to carry them upriver to see his property. Since they wouldn’t leave him in peace, he decided to make money off the visitors, capturing animals, holding them in cages, turning his property into a “zoo,” and charging an entrance fee. He did quite well until his death in 1968, ruled a suicide but still up for debate.

I got all this information from a park volunteer, sitting silently in the shadows, unseen by me while I pulled up my kayak and stomped around, desperately trying to find an appropriate location to relieve myself. It wasn’t until I’d finished, and started walking up the path to an interpretive sign that his radio crackled to life, scaring me half to death, and making me realize there was another human being only fifty feet away from me.

He was from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, but had been volunteering at Jonathan Dickinson for the last eight years. In those years, he’d never seen the water moving so fast. That made me feel much better.

After explaining the history of the location and talking about where he came from, he added, “And see that tall white building over there? That’s a working restroom.”

I walked around the property, through one of two cabins Nelson had built by hand, using the pine trees from his land. And I surveyed the cages, trying not to think about how awful it’d be for the animals imprisoned in these small, crude confinements. This was the highest ground I’d seen since launching—he’d chosen wisely. Along the river, it was lush. But it quickly turned into a sandy pine scrub landscape. He’d had the best of both worlds.

Back in my kayak, the river changed personalities instantaneously. The narrow, playful, twisty, private, secretive stream became a wide, slow-moving, mangrove-lined waterway capable of supporting motorized tour boats and fishing boats traveling up and down stream. Still beautiful, but far less charming.

Though tidal as far up as where I’d launched, the red mangrove trees signaled where the water became too brackish for Baldcypress to survive. The red mangrove incursion is a 20th century development. And, you guessed it, the change was caused by humans. The headwaters of the Loxahatchee is a slough which was drained for agriculture and housing developments in 1958. The canal that drains it reduced the fresh water flow in the Loxahatchee, allowing the saltier water to creep upstream, which had detrimental effects on the original flora and fauna. They are now working to restore the historical flow of the river which, they hope will allow the Baldcypress to reclaim its historical range.

As I neared the takeout, the river landscape changed yet again, well at least the east side did. There was a definite bank as opposed to the rest of the river, where the water, plants, and trees mixed to achieve a borderless effect. The few extra feet of elevation provided a foothold for tall pine trees and the low-growing scrub palmetto.

In only seven miles, I’d paddled through different epochs, different conditions, completely different plant communities, and an amazing amount of diversity.