The word ‘kayak’ originates from the Greenlandic word ‘qayaq’ and means ‘man’s boat’ or ‘hunter’s boat.’ A personal watercraft in every sense of the term, each man built his own boat frame made of either whale bone or drift wood to his specific size requirements and his wife sewed together the seal skin to fit over it. He made the cockpit two fists larger than his waist, the length was three of his arm spans, and the depth was his fist with an outstretched thumb. Yikes, talk about a tight fit!

These days procuring a kayak is as easy as clicking the keys on your computer. But some folks still want that personal connection. Coastal Kayak guide, Neil Baker, is one of those folks.

Appearance, according to Neil, was the main reason he wanted to build his own. “They’re really pretty,” he said.

Most people building their own kayaks these days purchase a kit. And most kits are made of wood. The two basic styles are cedar strip or stitch-and-glue plywood. Neil decided to go with the plywood because it goes together much faster. And the company he chose was Chesapeake Light Craft (CLC) because they are close—their showroom is in Annapolis.

Although handy at repairs, Neil had never done any wood-working. CLC assured him he didn’t need any special skills. He traveled to their showroom to look at the models, picked out the Shearwater 14, and a few weeks later a box (4’x4’x6”) showed up on his doorstep. He took one look at it and said, “There’s no boat in there.”

Two years later Neil opened the box. Once he got started, it took—with lots of starts and stops—about eighty hours to finish. He decided to make it a winter project and since his house doesn’t have a workshop, he built it in his 5’ by 20’ shed. It was such a small space he had to suspend half of the kayak from the ceiling when working on the other half.

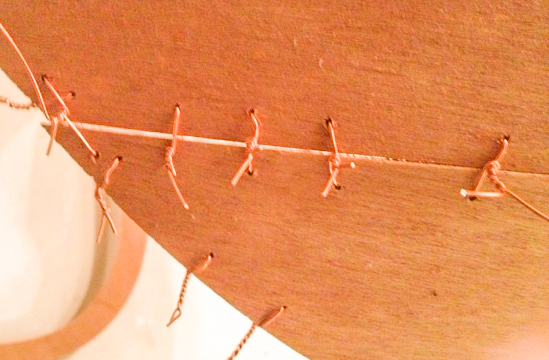

The “stitches” in the stitch and glue kayak kits are small gauge copper wire.

Neil’s boat design used jigsaw joints to piece the longer sections together.

The shiny, warm varnished wood is what is so eye-catching about these kayaks. But, according to Neil, the wood is just the frame. The fiberglass and epoxy are what gives the kayak its strength. And fiberglassing along with the never-ending sanding were the hardest parts of the project. Not so much hard, Neil says, as tedious.

The coolest part of the building process was fitting the top and the bottom together. “I’d been looking at these flat pieces wondering how they were going to make a curved deck. But then when I was putting them in place, they somehow just popped together and it looked exactly how it was supposed to,” Neil said.

Neil got hooked on kayaking about thirty years ago. A micro biology professor at Ohio State, he had summers off and used them to do research at Walter Reed in DC. Every Monday morning one of his colleagues told him about her weekend kayak adventures. Finally she agreed to take him on the Potomac. But only in the flat water. If he wanted to do more, she told him, he’d have to take a lesson. He did, and when he returned to Ohio, found some young guys into white water kayaking and hasn’t stopped paddling since. Over the years he’s lost track of the kayaks he’s bought and sold. But right now he has six—three white water boats, two fishing kayaks, and his newest addition—the wooden beauty he built with his own two hands.

Neil in his “man’s boat.”

“It paddles nice,” he said of his creation. “It’s as roomy and comfortable as a manufactured kayak.”

He admits he was apprehensive paddling it the first time but once he realized it would stay above the waterline, the feeling was awesome. “It was something I built, and it worked.”

For someone considering building a kayak who has never had any experience using tools, Neil admits it’d be hard to do it alone. But, according to Neil, there are two traits more important than anything else when it comes to taking on this project: Patience and perseverance.

The hull ready for epoxy.

The stitched deck.

Suspended action.

The top and bottom together!

Sand and varnish and sand and varnish and sand and varnish….

The sleekly beautiful finished product!